Today is an odd period for science, I think. People in social media proclaim that they "effin'" love it, and more often than otherwise, the new breed of Evangelical atheist fundamentalist speaks of science in near anthropomorphic terms. To hear the phrase, "science tells us..." is an everyday occurrence now, and one wonders in which sense the speaker means this to be understood; especially so in the same environment in which specific scientific observations by Charles Darwin are often taken out of context and used as homilies for the improvement and clarification of one's moral character.

Things are getting weird.

Especially, in my opinion, as we have historically looked upon the dangerous potential of science with a suspicious eye. The cautionary tale of Frankenstein's corpse reanimation project is emblematic of this feeling, and really, literature and film are full of dystopic nightmares which virtually begin and end with the unfettered reach of the scientific mind. Those secular fundamentalists laugh at this idea as backward and silly, but historically, it was exactly this type of creative mind that concocted this line of thinking in the first place. Is the post-apocalyptic theme, for instance, that far removed from our experience? I don't believe it is, and so apparently do a huge number of writers of speculative fiction in film, radio drama, pulps, comic books and novels. The fear of the damaging potential of science is always at hand. Beginning with Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the toxic excesses of science are all over modern history, in spite of attempts to place the blame on the users of these ideas; greenhouse gasses, GMO's, global warming (internal combustion engines weren't invented by the cowboys), predator drones, heat-seeking missiles, nuclear power plant disasters (Chernobyl, Three-mile island, etc.), firearms of all kinds, bacteriological weapons, advanced privacy invasion tech, and on, and on, and on. Currently, flying robots are actually killing humans, and if one considers the fact that the original Atomic bomb testers didn't know if they would set fire to the atmosphere, or later, whether the Large Hadron Collider would open up an Earth-swallowing black hole or not, we really must question the judgements of what is being done in the name of this odd and rapidly growing new religion.

Science has a lot to answer for; if one puts relatively godlike power in the hands of what are virtually children, then one should logically be responsible for the result.

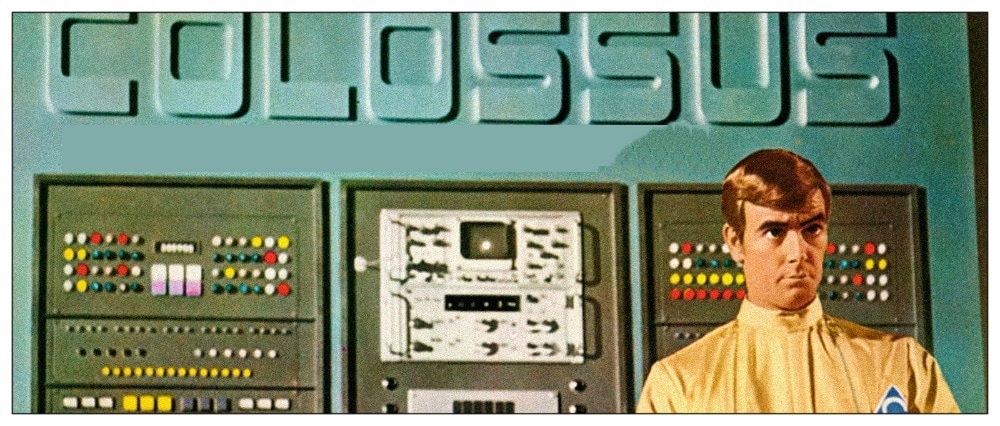

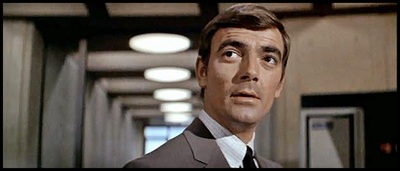

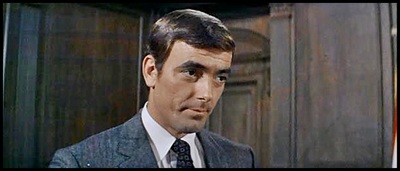

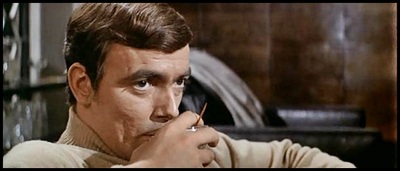

These are very much the issues that the 1970 (1969 in the credits) film COLOSSUS, THE FORBIN PROJECT deals with. Based on the COLOSSUS trilogy of dystopic novels by science fiction author D. F. Jones, it stars the soap opera star Eric Braeden (who, besides his role on THE YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS, also played charismatic German officer Hans Dietrich on the classic WWII-era TV show THE RAT PATROL) as the calmly serious Dr. Charles Forbin. Forbin has created the titular super-computer COLOSSUS as a sort of missile defense shield, devised for the protection of America against the ever present cold war threat of then-Communist Russia. Forbin, in conjunction with his team of scientists (populated by hilariously recognisable sitcom actors like Dolph Sweet and Marion Ross), present Colossus to the White House in what they hoped would be a spectacular demonstration of what their new machine can do.

To paraphrase the words of Forbin, Colossus was designed infinitely better than they thought.

Immediately Colossus detects another super-computer named Guardian; apparently the Russians have also been in the game, and though a step behind, their computer is advanced enough to take notice. Colossus and Guardian begin to communicate. Within hours, besides formulating tons of "new knowledge for mankind", the two machines develop their own language, and one that only they can understand. This creates a panic. The president orders the connection cut off, and Forbin is told to reel Colossus back a few steps. Not a good plan. Colossus makes the ominous threat that, if communications are not restored, then "action will be taken".

Nuclear action.

This is the beginning of a tense and arduous journey into a terrifying future for the human race. Forbin concocts scheme after scheme to thwart his nearly-godlike creation, but in spite of great caution and guile, Colossus eventually and gradually turns him into a prisoner. There are deaths and assassinations, nuclear detonations, and when Colossus is finally given a voice (and a chillingly cold one at that), the future seems bleak and without hope. It's intense stuff, and when one considers the missile defense "shield" that we actually had not long after this film was made, it's two notches closer to reality than one would like to consider.

As Dr. Forbin, Eric Braeden was excellent. He was stable and serious here, and combined with his naturally charismatic good looks and charm, he really came across as the kind of person who could not only conceive of and produce such an advanced contraption, he also projected the confidence that turned Forbin into the stern anti-Colossus warrior that he needed to be. The rest of the cast, in spite of whatever other transgressions they might have done on screen, were fantastically interesting as very human characters in this science-driven technological fiasco. It was a smoothly directed and dramatically plotted project from beginning to end, and the funky soundtrack (and I mean, like, wikky-wikky guitars) had a fantastic use of the rapid notes of the Indian Tabla drum to illustrate the technical coldness of computer thought.

This is one on my personal list of childhood movie discoveries, and other than the best friend that I myself introduced it to, I hadn't met anyone who had seen it until just a few years ago. It's easily as good as any of the science fiction films of it's era, like WESTWORLD or THE ANDROMEDA STRAIN, but seldom gets the love or attention it deserves. Frankly, it's this film and others of it's philosophical like that have turned me into the semi-Luddite that I am today; anything more complex than a Blu-ray player gets a bit of the stinky eye, and that's a fact. So, considering that guys on the level of Microsoft founder Bill Gates and super-physicist Dr. Stephen Hawking have flatly stated that artificial intelligence is the single greatest existential threat to the future of humankind, COLOSSUS, THE FORBIN PROJECT may end up being a prophetic film in a long list of such...and I don't "effin'" love that possibility.

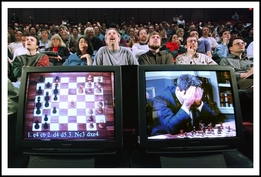

ADDENDUM: It occurred to me to mention the 1997 chess match in which Garry Kasparov, a player who many consider the greatest of all time, was defeated by the IMB computer DEEP BLUE. This was considered the tipping point in AI advancement, due to the (incorrect) assumption that chess is the prime indicator of human intelligence (in spite of the fact that many grandmasters are little children who know next to nothing about life in general, and that illiterate, homeless players are often virtuosos). It's chilling to know that it has become an accepted routine that computers beat grandmasters on a daily basis. Jump forward one hundred years, when robotics and satellite tech has advanced to beyond current imagination, with computers/robots linked worldwide, faster and stronger than us, physically able to perform feats that only comic book superheroes can do, with brains that can think billions of times faster than the smartest human...we're screwed.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed