Byomkesh Bakshi

Byomkesh Bakshi In the common speech of the people of the Indian subcontinent, the Sanskrit-derived term "Desi" (pronounced "dey-see") is a catch-all for the people or things that originate in that region. Desi countries include Pakistan, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh. I think it's an amazing word; it unites, through cultural commonalities, a multitude of disparate groups that are often at odds politically...the obvious example being India and Pakistan. It's a nice lens with which to examine and understand an amazingly diverse part of the world.

I came to Desi culture though a side door. As a kid I was obsessed with Victorian and Edwardian English novels, especially those amazing tales of adventure set in what I perceived at that time to be "exotic, far-off lands". Considering the fact that a significant portion of the globe was under the British thumb at the time those books were written, I was exposed to quite a bit; the sun never sets on the British Empire, wot? For better or worse, from a political perspective, the then-called "British Raj" (Raj means "reign" in Hindi') opened my eyes to a number of beautiful lands for the first time.

Of course, everything was presented through the filter of a British mind; most of the Desi-type characters I knew in those days, including Gunga Din and my beloved Rikki-Tikki-Tavi, were the product of an occupation. As I grew and dug deeper, I found it amazingly difficult to find literature and film directly from a Desi source. Though it's tempting to blame patterns of racism, etc. inherent to such an occupation, I've found that much of the difficulty can also be attributed to ethno-linguistic provincialism; there is simply not that much of this stuff available outside their areas of origin or in languages other than the original.

I came to Desi culture though a side door. As a kid I was obsessed with Victorian and Edwardian English novels, especially those amazing tales of adventure set in what I perceived at that time to be "exotic, far-off lands". Considering the fact that a significant portion of the globe was under the British thumb at the time those books were written, I was exposed to quite a bit; the sun never sets on the British Empire, wot? For better or worse, from a political perspective, the then-called "British Raj" (Raj means "reign" in Hindi') opened my eyes to a number of beautiful lands for the first time.

Of course, everything was presented through the filter of a British mind; most of the Desi-type characters I knew in those days, including Gunga Din and my beloved Rikki-Tikki-Tavi, were the product of an occupation. As I grew and dug deeper, I found it amazingly difficult to find literature and film directly from a Desi source. Though it's tempting to blame patterns of racism, etc. inherent to such an occupation, I've found that much of the difficulty can also be attributed to ethno-linguistic provincialism; there is simply not that much of this stuff available outside their areas of origin or in languages other than the original.

Thus, being a huge consumer of detective fiction in that pre-internet world, I had always found "the East" to be, if one may pardon the expression, "inscrutable" as far as any clear information went. I had always heard that there were homegrown Asian detectives, but most of what I'd heard about came from western sources. Charlie Chan, Mr. Moto, and even Judge Dee, were the creations of Caucasian writers (most of the Judge Dee stories were created by Robert Van Gulik). Yet, in various detective fiction periodicals, I would get tantalising suggestions of Asian mystery; I mean, who wouldn't want to read Swapankumar's stories of the (reportedly) amazing detective Deepak Chatterjee, who was, among other things, a polyglot martial arts expert? Even now, when a few of those stories are accessable, a knowledge of written Bengali would be the only way to enjoy these untranslated masterworks.

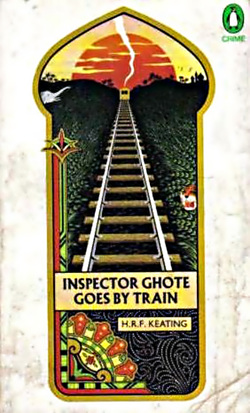

So, lacking any options, my first Desi-type detective was the unshakeable Inspector Ghote, also written by another Englishman, H. R. F. Keating. I loved the first one that I found, Inspector Ghote Goes By Train. It was an amazing read! Ghote is assigned the task of escorting a wily grifter by train from Calcutta to Bombay, and nothing goes exactly as planned...but in a highly entertaining and complex way. It really was a great book, but still not the genuine Desi article. Still, hungry for that world, I read as many of them as I could find. Ghote remains one of my favourite characters in fiction, in spite of that minor issue of authenticity; if I'm correct, Keating hadn't yet been to India when he wrote the first book! In any case, I was recently delighted to find that the filmmakers Ismail Merchant and James Ivory had made an Inspector Ghote film, and that there was a 1983 episode of the British anthology series Storyboard featuring Ghote, as well as a number of wonderful radio dramatisations of the stories.

So, lacking any options, my first Desi-type detective was the unshakeable Inspector Ghote, also written by another Englishman, H. R. F. Keating. I loved the first one that I found, Inspector Ghote Goes By Train. It was an amazing read! Ghote is assigned the task of escorting a wily grifter by train from Calcutta to Bombay, and nothing goes exactly as planned...but in a highly entertaining and complex way. It really was a great book, but still not the genuine Desi article. Still, hungry for that world, I read as many of them as I could find. Ghote remains one of my favourite characters in fiction, in spite of that minor issue of authenticity; if I'm correct, Keating hadn't yet been to India when he wrote the first book! In any case, I was recently delighted to find that the filmmakers Ismail Merchant and James Ivory had made an Inspector Ghote film, and that there was a 1983 episode of the British anthology series Storyboard featuring Ghote, as well as a number of wonderful radio dramatisations of the stories.

In my early twenties I finally had the access that I had longed for, and began to dig into the broader world of South Asian culture. In the decades afterward I studied the Indian tabla with a variety of teachers (including the legendary Zakir Hussein), met the Shahen Shah (king of kings) of Qawwali music, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan (through the Ethnomusicology department at the University of Washington), I bought a mountain of recordings of Carnatic kritis, of Drupad, Khyal, Ghazel, and Thumri, and watched a ton of films in various Desi languages, my favourite being the Sindhi director G. P. Sippy's classic action masterpiece, SHOLAY ("maa ney tumhara namuk kaya hai, serdar..."). I learned a good deal of Urdu/Hindi/Punjabi (never could get a grip on Tamil), and finally ended up going to Pakistan (Lahore, Islamabad and Karachi), and India (Chennai, Mumbai, New Delhi, Lucknow, Amritsar and all points in between) several times, in a whirlwind of colour and excitement. It was during the initial portion of that period that an Indian friend loaned me a paperback collection of mystery stories by the Bengali writer Sharadindu Bandyopadhyay.

At last, I had actual Desi mysteries in English! The detective was the famous Byomkesh Bakshi the Satyanweshi, or "truth seeker", who solved puzzle-like crimes in over thirty stories written between 1932 and 1970, accompanied by his friend and observant Boswell, the excellently Dr. Watson-ish Ajit Banerjee. I was trapped in my chair from page one; the translation really captured the ambiance of that world that I'd learned to love so well, and the mysteries were both peculiar and satisfying.

Though Bandyopadhyay apparently bemoaned the "Englishness" of the Desi detectives written in the forty years before his time, Byomkesh has a great many Sherlock Holmes-ish traits, though with a uniquely Desi flair. He's an obsessive thinker, thrives on a complex problem, he delights in the mild confusion of his less-observant friend, and he paces about smoking (Cigarettes, not a pipe), when on a case. Like every other mystery writer, Bandopadhyay's writing was greatly inspired by Arthur Conan Doyle (as well as by Agatha Christie and G. K. Chesterson), so one can forgive a comparison or two. In the end, what transforms the archetype into a fresh character is both the context and the magical alchemy of Byomkesh's idiosyncrasies.

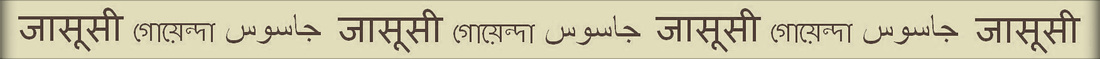

A great thing about these stories is that translations in English are easy to acquire; a casual search online will lead to a variety of well-printed editions. I'd really love to be able to read Sharadindu Bandyopadhyay's writing in the original Bengali; though the translations are evocative and highly readable, there are hints of missing flavours that leave me longing for more. The only Bengali word that I know, in fact, is Goyenda, meaning detective ("Jasoosi" in Nepali, Urdu & Hindi), and while appropriate to this context, I lack the 9,999 other words needed for a satisfying reading experience.

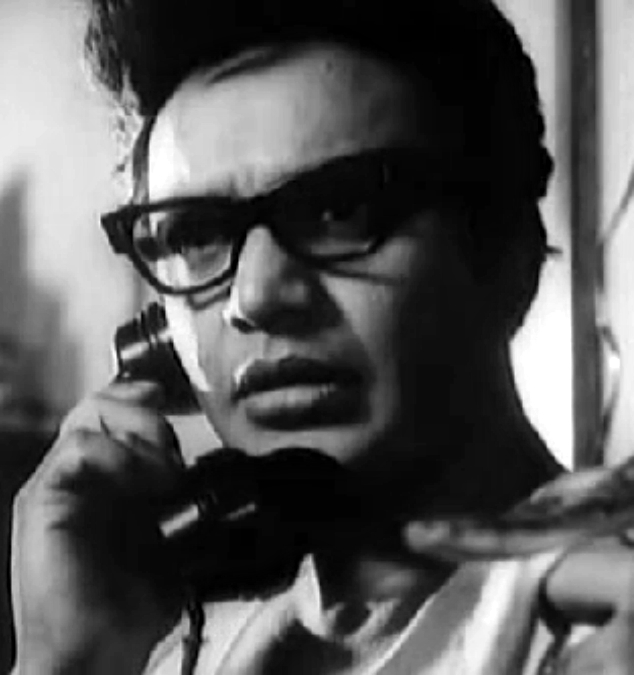

I've come to learn that Byomkesh is quite famous across the Desi universe, and his detections have been made into a number of movies. One of these, called Chiriyakhana (meaning "the Menagerie"), was made in 1967 by Satyajit Ray, one of the most famous Indian writers and movie directors of all time. The film snobs, of course, consider it his worst film, probably because it is both fun and interesting; I've seen it (and will review it soon), and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Since Chiriyakhana, the Byomkesh character has been featured in many other films, and was also made into a well-liked television series.

Though Bandyopadhyay apparently bemoaned the "Englishness" of the Desi detectives written in the forty years before his time, Byomkesh has a great many Sherlock Holmes-ish traits, though with a uniquely Desi flair. He's an obsessive thinker, thrives on a complex problem, he delights in the mild confusion of his less-observant friend, and he paces about smoking (Cigarettes, not a pipe), when on a case. Like every other mystery writer, Bandopadhyay's writing was greatly inspired by Arthur Conan Doyle (as well as by Agatha Christie and G. K. Chesterson), so one can forgive a comparison or two. In the end, what transforms the archetype into a fresh character is both the context and the magical alchemy of Byomkesh's idiosyncrasies.

A great thing about these stories is that translations in English are easy to acquire; a casual search online will lead to a variety of well-printed editions. I'd really love to be able to read Sharadindu Bandyopadhyay's writing in the original Bengali; though the translations are evocative and highly readable, there are hints of missing flavours that leave me longing for more. The only Bengali word that I know, in fact, is Goyenda, meaning detective ("Jasoosi" in Nepali, Urdu & Hindi), and while appropriate to this context, I lack the 9,999 other words needed for a satisfying reading experience.

I've come to learn that Byomkesh is quite famous across the Desi universe, and his detections have been made into a number of movies. One of these, called Chiriyakhana (meaning "the Menagerie"), was made in 1967 by Satyajit Ray, one of the most famous Indian writers and movie directors of all time. The film snobs, of course, consider it his worst film, probably because it is both fun and interesting; I've seen it (and will review it soon), and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Since Chiriyakhana, the Byomkesh character has been featured in many other films, and was also made into a well-liked television series.

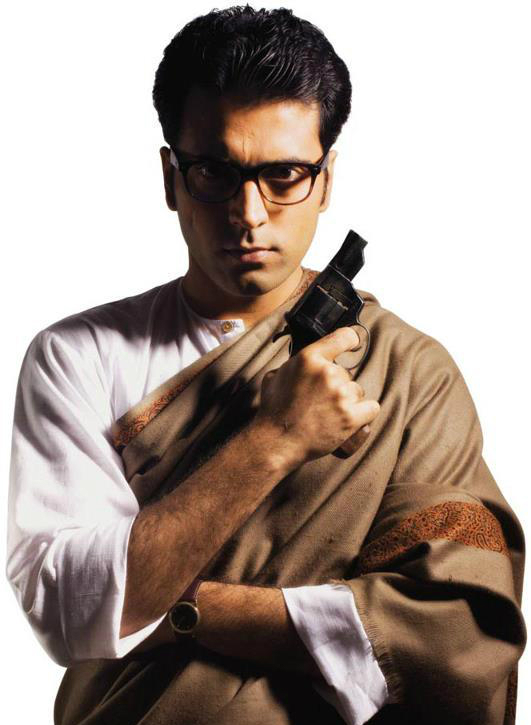

Some of the many film faces of Byomkesh Bakshi

At that point in my pursuit of this kind of fiction, my Indian and Pakistani friends were quite happy to make suggestions to me. I quickly found out that Byomkesh Bakshi was just the tip of a small, but entertaining iceberg. A co-worker brought me a surprise one day, in the form of a mystery collection by the afore-mentioned Satyajit Ray, introducing another Bengali detective, Prodosh Chandra Mitra, nicknamed Feluda.

Feluda is another very Holmesian figure; he has as his Watson character his cousin Tapesh, he openly admires Holmes in the books, and among many other things, he lives at 21 Rajani Sen Road, in loving homage to 221B Baker street. Other than those fun nods to the master, Feluda is very much his own man. Though he prefers to use his powerful mind to solve a case (with what he reportedly refers to as his Magajastra or "brain weapon"), he's also a fearless man of action who carries a revolver and is skilled in the martial arts.

Feluda is another very Holmesian figure; he has as his Watson character his cousin Tapesh, he openly admires Holmes in the books, and among many other things, he lives at 21 Rajani Sen Road, in loving homage to 221B Baker street. Other than those fun nods to the master, Feluda is very much his own man. Though he prefers to use his powerful mind to solve a case (with what he reportedly refers to as his Magajastra or "brain weapon"), he's also a fearless man of action who carries a revolver and is skilled in the martial arts.

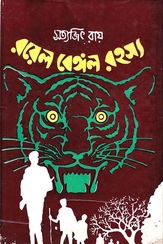

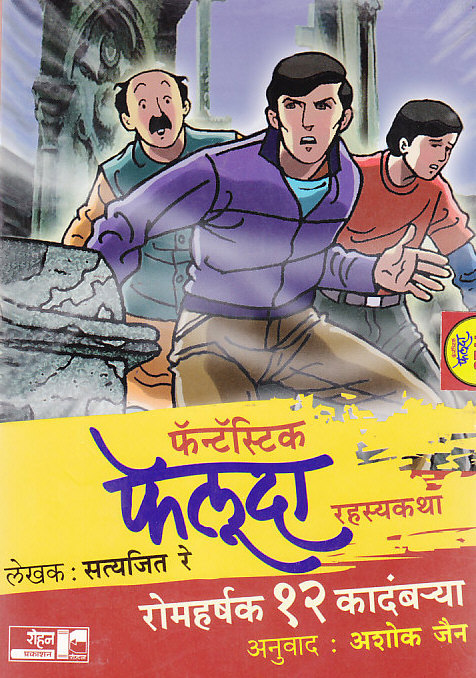

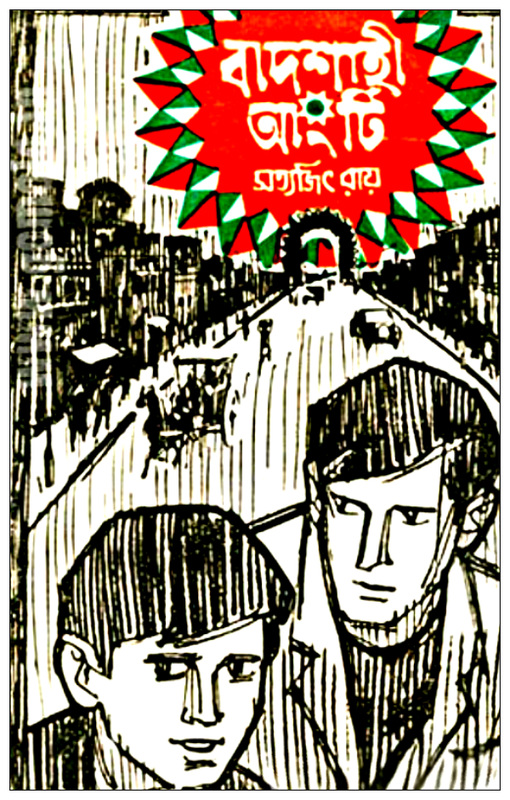

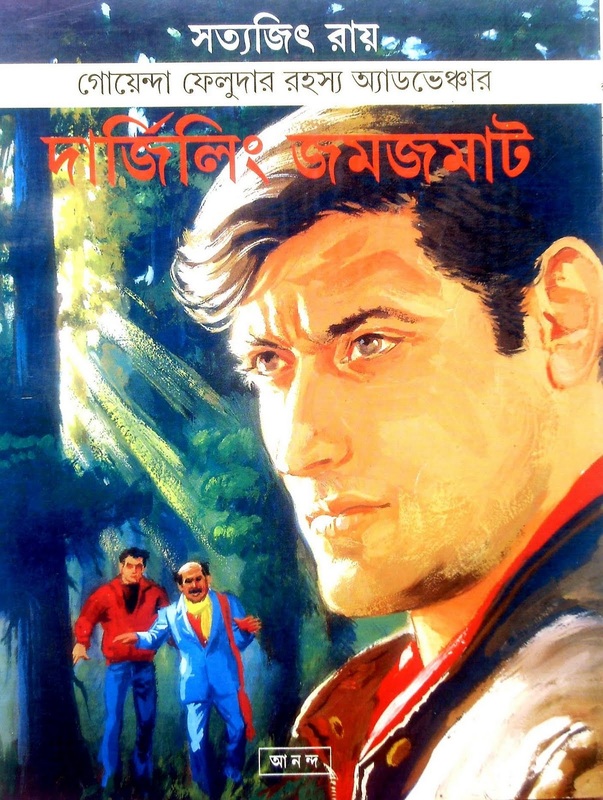

A Feluda "Royal Bengal" mystery

A Feluda "Royal Bengal" mystery Feluda is featured in over thirty novels and stories, as well as at least eight films (directed by Sandeep Ray, Satyajit Ray's only son), a number of radio dramas, and a multitude of television productions.

After having seen so many of Satyajit Ray's movies (especially my favourite, Shatranj Ke Khiladi "The Chess Players", from 1977), I was stunned to find that he had a parallel career in writing detective fiction. I would say, from what I've been able to ascertain, that his writing life was as famous in the Desi world as that of his filmmaking...or at least as prolific and visible. In fact, like the Byomkesh stories, a great many of the Feluda tales are readily available in nice translations.

After having seen so many of Satyajit Ray's movies (especially my favourite, Shatranj Ke Khiladi "The Chess Players", from 1977), I was stunned to find that he had a parallel career in writing detective fiction. I would say, from what I've been able to ascertain, that his writing life was as famous in the Desi world as that of his filmmaking...or at least as prolific and visible. In fact, like the Byomkesh stories, a great many of the Feluda tales are readily available in nice translations.

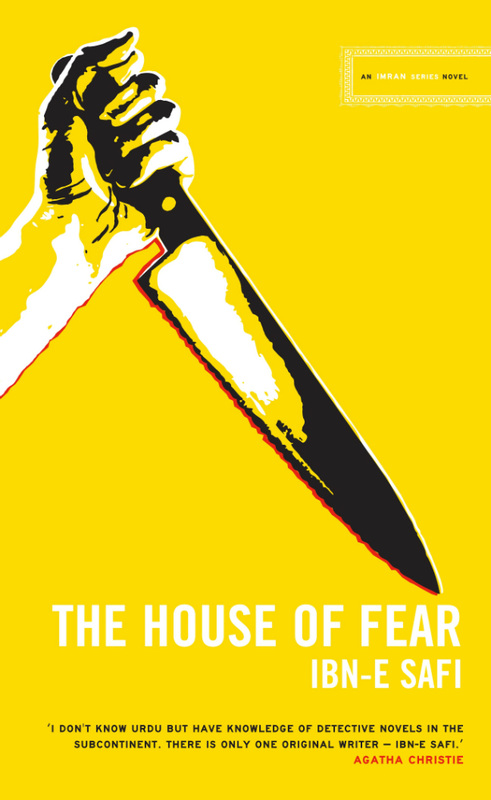

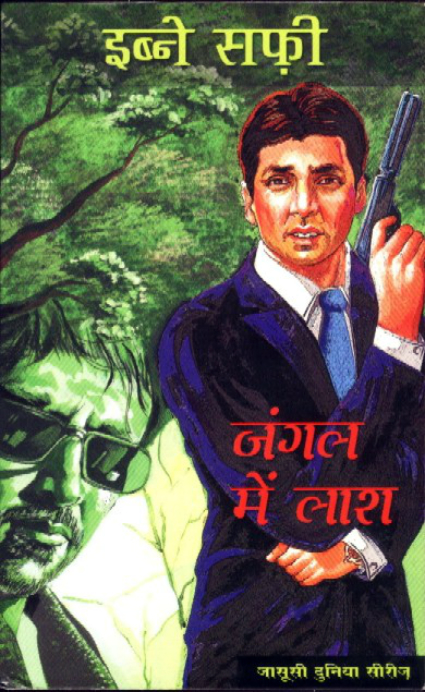

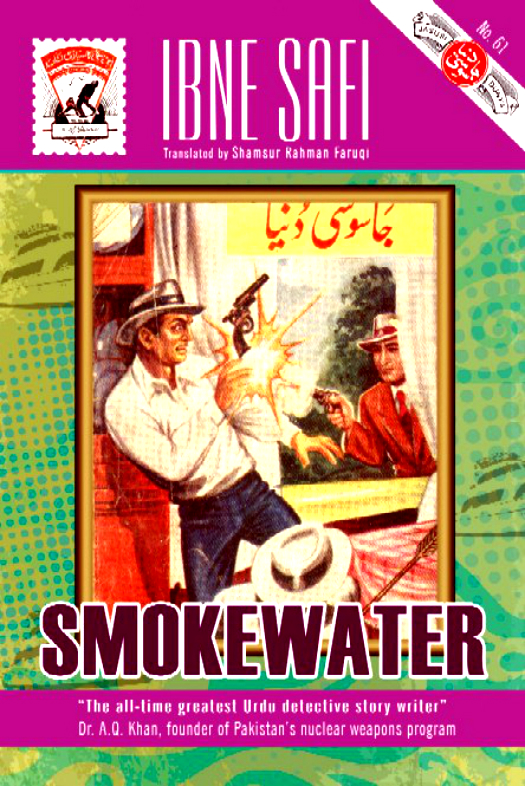

The final Desi writer that I'll share here is Ibn-e Safi, the nom de plume of Asrar Ahmad. He was recommended to me very enthusiastically by several Pakistani friends. Safi was insanely prolific; he wrote 245 Urdu-language books throughout his lifetime, nearly equally divided between his two major series. Those series are Jasoosi Dunya (The Detective/Spy World), featuring the dapper, Oxford-educated man-about town Inspector/Colonel Ahmad Kamal Faridi, and the Imran series, with the Handsome and eccentric Ali Imran, a P.H.D. in chemistry with a deceptively comical demeanor, who also happens to be X-2, the secret head of the secret service.

Being Pakistani, both characters are stoutly Muslim, as are their formidable sidekicks. As a Muslim myself, I like that. Colonel Faridi is backed up by the mischievously argumentative, yet fearless, Sergeant Hameed. Hameed, though he amuses himself by irritating Faridi, is, by all accounts, completely loyal...to the death. Imran, as written by Ibn-e Safi, has as his bodyguard the ex-boxer, Joseph Magonda; a heavy drinking black African (as opposed to Desi African; there is a huge population of Desi people all over Africa). Joseph, though he came to Faridi by way of his having been defeated in a fight, is also dedicated to Imran, to the point of considering him his father. Imran, at the pen of Ibn-e Safi's successor, Mazhar Kaleem (who has written at least 500 books in the Jasoosi Dunya world!), has as his disciple the devoted Rizwan, known as "Tiger". Tiger is a martial arts expert, and is so capable and so shadows his hero, that he's dubbed "Imran #2'. Of course there are many other characters that support both Faridi and Imran in their adventures, who offer not only valued assistance, but also great narrative colour to the stories.

Both of these are highly enjoyable and unique reads overall. Ibn-e Safi had a flair for finding the colour in a story, and if a story begins to falter, there is always some completely random element tossed in to spice it up. I've read two Faridi books and one in the Imran series (though it wasn't by Ibn-e Safi, but by Mazhar Kaleem), and I enjoyed all three of them. Once again, there are wonderful printings available online for very reasonable prices.

Of the writers I've mentioned, I wouldn't suggest starting with Ibn-e Safi if you're only mildly exposed to South Asian culture; his stuff is deep Desi, and a little background in the wild and peculiar world of the art of the subcontinent will go a long way in preparation for these potent fables.

Being Pakistani, both characters are stoutly Muslim, as are their formidable sidekicks. As a Muslim myself, I like that. Colonel Faridi is backed up by the mischievously argumentative, yet fearless, Sergeant Hameed. Hameed, though he amuses himself by irritating Faridi, is, by all accounts, completely loyal...to the death. Imran, as written by Ibn-e Safi, has as his bodyguard the ex-boxer, Joseph Magonda; a heavy drinking black African (as opposed to Desi African; there is a huge population of Desi people all over Africa). Joseph, though he came to Faridi by way of his having been defeated in a fight, is also dedicated to Imran, to the point of considering him his father. Imran, at the pen of Ibn-e Safi's successor, Mazhar Kaleem (who has written at least 500 books in the Jasoosi Dunya world!), has as his disciple the devoted Rizwan, known as "Tiger". Tiger is a martial arts expert, and is so capable and so shadows his hero, that he's dubbed "Imran #2'. Of course there are many other characters that support both Faridi and Imran in their adventures, who offer not only valued assistance, but also great narrative colour to the stories.

Both of these are highly enjoyable and unique reads overall. Ibn-e Safi had a flair for finding the colour in a story, and if a story begins to falter, there is always some completely random element tossed in to spice it up. I've read two Faridi books and one in the Imran series (though it wasn't by Ibn-e Safi, but by Mazhar Kaleem), and I enjoyed all three of them. Once again, there are wonderful printings available online for very reasonable prices.

Of the writers I've mentioned, I wouldn't suggest starting with Ibn-e Safi if you're only mildly exposed to South Asian culture; his stuff is deep Desi, and a little background in the wild and peculiar world of the art of the subcontinent will go a long way in preparation for these potent fables.

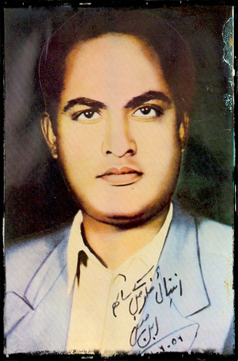

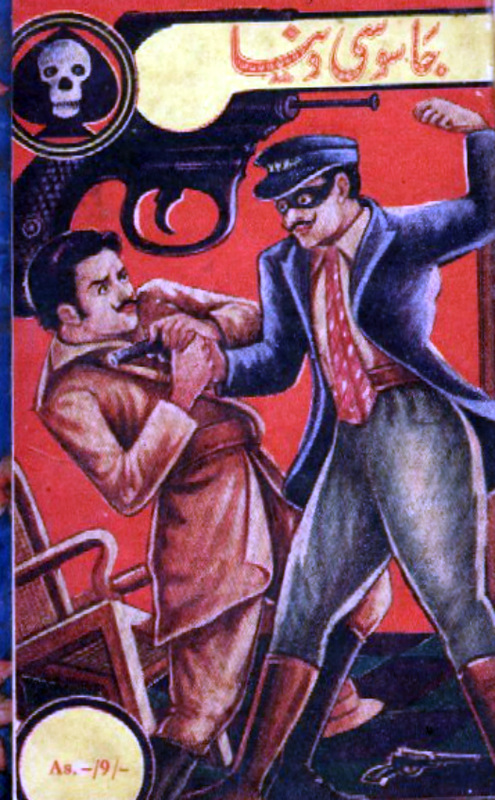

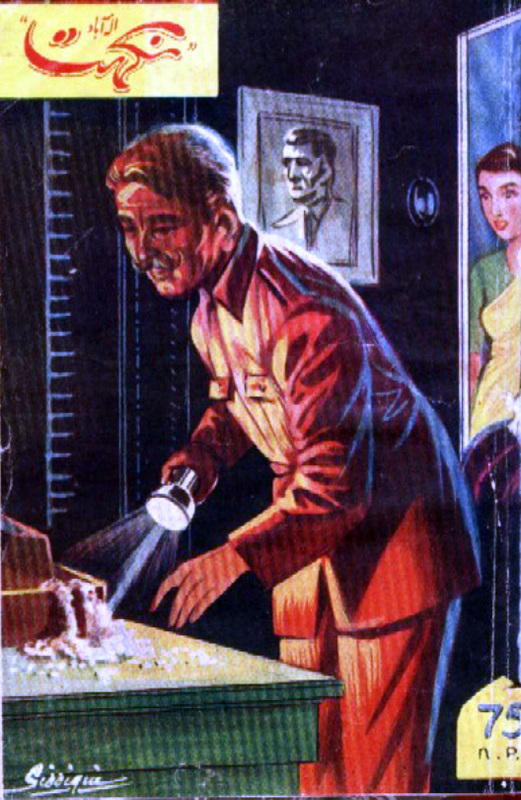

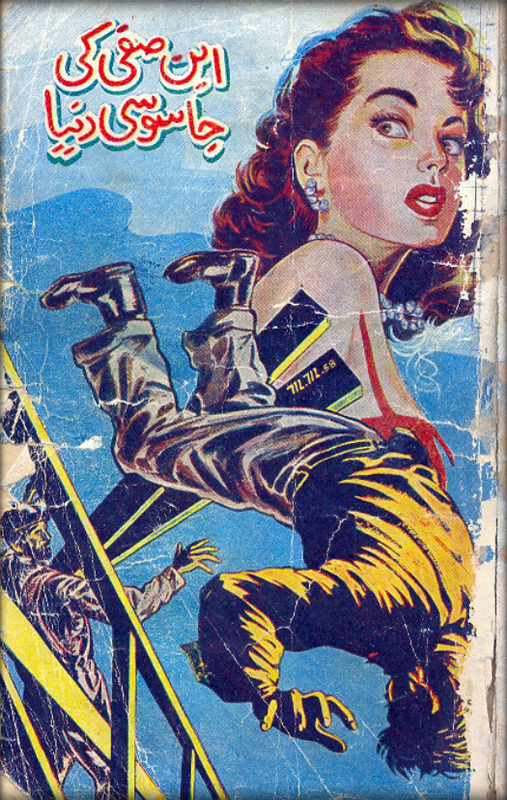

Here are some of the many amazing Ibn-e Safi original covers:

There are many other wonderful Desi detectives that I haven't detailed here; a part of this huge list would include:

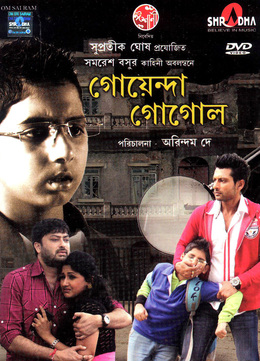

- Samaresh Basu's child detective, Gogol, who has been dramatised in the 2013 film Goyenda Gogol,

- The first female English detective in India, written in the 1940's, Detective Janaki, by Kamala Ratnam Sathianadhan,

- The two Tamil detective duos, Pattukkottai Prabakar's Bharat and Susheela, and Subha's (the joint pen-name of D. Suresh and A. N. Balakrishnan) Narendran and Vaijayanthi, of the Eagle Eye Detective agency,

- and a quite recent Punjabi detective, the mustachioed rake Vish Puri, written by Tarquin Hall (an Englishman who, unlike H. R. F. Keating, actually lives in India).

It occurs to me as I'm writing this, that though the British colonisation of India was a pretty insufferable period, some very English things were introduced that Desi people have truly made their own. That the game of Cricket is insanely popular in all of those countries is a perfect example. I'm gratified to see that a few good things, such as the detective story, were taken out of that situation and transformed into something uniquely South Asian; I like to think that British writers like Conan Doyle and Dame Agatha would be pleased by the charismatic works of their former colonial cousins.

Here are some useful links to more info about this amazing stuff; I share them with gratitude to those that wrote all that interesting info. I've been very lucky to find an access point into this great little universe, and I hope that you've found something here of interest. It's been a long and interesting little branch of my life-path, and it really shows, in microcosm, how incredibly diverse the world really is.

Here are some useful links to more info about this amazing stuff; I share them with gratitude to those that wrote all that interesting info. I've been very lucky to find an access point into this great little universe, and I hope that you've found something here of interest. It's been a long and interesting little branch of my life-path, and it really shows, in microcosm, how incredibly diverse the world really is.

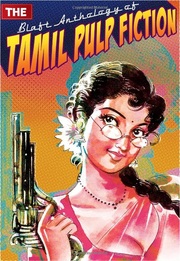

I'd also like to mention two great collections of translations of Tamil-language pulpy goodness, the Blaft Anthologies of Tamil Pulp Fiction. They're quite wonderful with a broad range of incredible stuff. Both are available online, and are very reasonably priced! Click on images for links.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed